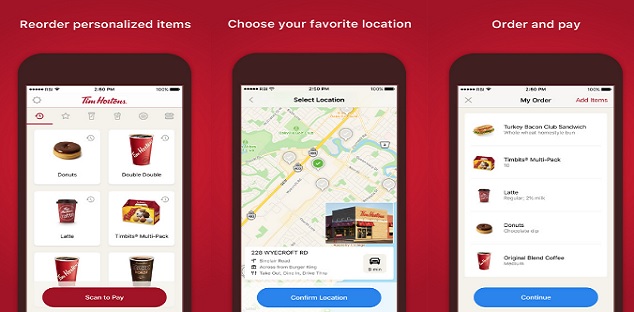

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada recently announced plans to investigate the Tim Hortons mobile app. A comprehensive media report released mid-June prompted this investigation. It brought up concerns about how the company collects data from its users and the amount of information it receives—even without the customers being on the app.

The federal Privacy Commissioner will be working with three of its provincial counterparts in Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta to determine whether the app complies with the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). PIPEDA is Canada's federal private sector privacy law.

They want to determine if Tim Hortons received "meaningful consent" from app users, meaning companies can only collect information if they receive consent from the individuals affected.

"To make the consent meaningful, the purposes must be stated in such a manner that the individual can reasonably understand how the information will be used or disclosed," PIPEDA states.

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada is concerned about the privacy issue this practice raises, particularly when it comes to geolocation data gathering. Geolocation data offers sensitive information about habits and activities, like medical visits and the places they frequent. And they want to determine if it's appropriate to collect and use this data under these circumstances.

Financial Post's James McLeod brought up this problem after discovering the app was collecting more information than what's perceived as necessary from millions of its users. McLeod used PIPEDA to request his data from Tim Hortons' parent company Restaurant Brands International Inc., which then gave us a look at just how much data the coffee and fast-food chain collects from the users of its mobile app.

He discovered that the company had recorded his longitude and latitude coordinates over 2,700 times in less than five months, even when he wasn't using the app.

McLeod received vast amounts of text files containing thousands of computer code pages in a format known as JavaScript Object Notation (JSON). He received information from November 2018 to October 2019. According to the data he collected, many of the information pulled off from his phone and logged in RBI servers recorded his interactions with the app from launching it through to checkout.

The data also showed Tim Hortons using a location-tracking service from Radar Labs Inc. The company claims on its site to ping phones carrying its tech as often as every three to five minutes.

The app recorded the type of device he was using (a Pixel 3XL), Android Advertising ID, and carrier. It routinely logged hi IP address and when he had Bluetooth enabled. There were lines of code that even listed the amount of free disk space he had and how much charge the battery was holding.

"Radar, as described, is turning your phone into a device that's constantly streaming your location to a remote server. It's unexpected. It's certainly far more invasive than I would consider acceptable for a coffee shop app. I don't think any of us want corporations watching every single move we make without any insight into it." —Erinn Atwater, research and funding director at Open Privacy

According to Tim Hortons Chief Corporate Officer Duncan Fulton, users consent to this tracking when they allow the app to access the GPS on their phone, and the onus was on the user to deny the app such access.

When McLeod checked the Tim Hortons app's FAQ on privacy issues, it said that it tracked location "only when you have the app open." But as it was revealed in the data he received, Tim Hortons was getting information even when he wasn't on the app. That statement remained on the app until the week the article came out on June 12.

And when Financial Post clarified the discrepancy, the media outlet claimed Tim Hortons revised its privacy statement to say that users' ability to limit location tracking differs "depending on your device." And that its users should "check and understand your device settings" to make sure they are comfortable with the amount of location information they're sharing. The company did acknowledge that statement was misleading.

"We absolutely agree that our FAQ on location data could have been more clear," Fulton said. He added that Tim Hortons sent an updated statement to customers.

When you check the Tim Hortons app now, it states: "It's up to you to decide if you want to share your location data. Depending on your device, you will have different options about how to share this data… Make sure you check and understand your device settings to be sure they reflect your preference."

The company sent an email to its app users informing them that in addition to using location data to route orders to the nearest restaurant: "We'll use your location data to provide you with tailored offers and choices. For example, we may provide you different offers depending on the community where you live, or we may send you a tailored offer on your morning commute."

Fulton has been quoted in the story that this kind of data collection isn't out of the ordinary.

"We are not on the cutting edge of this. We are the blunt edge of a butter knife compared to cutting-edge collection and use of data," he said.

McLeod showed his data to Erinn Atwater, research and funding director at Open Privacy, a non-profit organization based in Vancouver that advocates for better privacy and security practices. Atwater confirmed his understanding of the JSON data and was surprised to discover that Radar is conducting server-side location processing. It allowed the app to send streams of location data to Radar, which they then analyzed and sent back "items of interest" to RBI.

"Radar, as described, is turning your phone into a device that's constantly streaming your location to a remote server," Atwater said. "It's unexpected. It's certainly far more invasive than I would consider acceptable for a coffee shop app. I don't think any of us want corporations watching every single move we make without any insight into it."

The amount of information collected might already be concerning, but the report also raises the issue of RBI using partners to gather data.

Radar isn't the only company RBI is working with. Atwater pointed out companies like Amplitude Inc., Braze Inc., and mParticle Inc. provided services to Tim Hortons to help track its users. Fulton confirmed this list, but he also said it doesn't sell its data, even in anonymized form. He then acknowledged that they buy other data sets to get a better insight into consumer activity.

Fulton said customer location data is usually kept for 12 months, but that the company has safeguards in place to ensure that not all customers can access detailed customer location information.

"There's actually only a very few number of people in the company that would have access to all the different information silos," he said. "And we routinely run a monthly audit on every access to every part of our information databases. So we can see on a monthly basis who is accessing which data for what reason."

Why go through this trouble of gathering this much data? It's a big part of RBI's business plan over the past couple of years. McLeod wrote, "The app, which is inexorably tied to the Tim Hortons loyalty program, is a huge part of it."

The data RBI gets offers them better insight into their consumers. It can learn customers' habits and preferences that will hopefully keep them coming back. It is, as Fulton, pointed out isn't exactly an unusual business move.

"We are not on the cutting edge of this. We are the blunt edge of a butter knife compared to cutting-edge collection and use of data." —Duncan Fulton, Tim Hortons chief corporate officer

But it has been something privacy experts have been concerned about for a long time. Tech giants Apple and Google, who operate platforms iOS and Android, have responded to this issue.

Since 2014, Apple has given the users the ability to limit how apps can access location data. It's something they've doubled down on with the recently announced iOS 14.

As for Android, McLeod pointed out that location permission was a "blanket all-or-nothing" when he signed up for the Tim Hortons app. It's only Android 10—which is the latest version of the operating system—that offers granular location permissions. This feature allows users to dictate whether services like location permission are only enabled when the app is in use or all the time. The feature is also what tipped him to the issue in the first place.

Unfortunately, users running an older version of Android are stuck with either giving blanket access to background tracking or deny location permission entirely, which could render certain features in apps almost unusable.

Google is tackling background tracking further with a new policy it's enacting by November.

"An app with a store locator feature would work just fine by only accessing location when the app is visible to the user," the Android Developers Blog post said when it announced the upcoming policy. "In this scenario, the app would not have a strong case to request background location under the new policy."

All existing apps that access location in the background will require Google's approval or these apps will be removed from the Google Play Store.

Despite this, Fulton said RBI doesn't plan to offer an opt-out of tracking for marketing purposes if they choose to enable location services to use the store locator function.

So, for those who can still only give blanket access to the app, you might have to think about whether you're willing to provide that much data to a company.